The Vānaprastha Adventure, Installment 6

The Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam presents historical examples of great souls who accepted the vānaprastha āśrama. Though we may not live the same way as them, their path can serve to instruct us. Here I will only mention some of them. But we can go to the Bhāgavatam to read further.

We have already mentioned King Dhṛtarāṣṭra, who at the end of his life gave up his illusions and left for the forest for spiritual realization.1 He was able to do this by the grace of Vidura, who himself had turned his back on political life and set out on pilgrimage.2 While serving as a faithful advisor to the Kauravas, Vidura had been bitterly insulted by Duryodhana. Seeing this as an opportunity made possible by the grace of Kṛṣṇa’s energies, Vidura had left home to devote himself entirely to Kṛṣṇa’s service. Vidura in his travels met the saint Maitreya, from whom he received enlightening spiritual instructions.

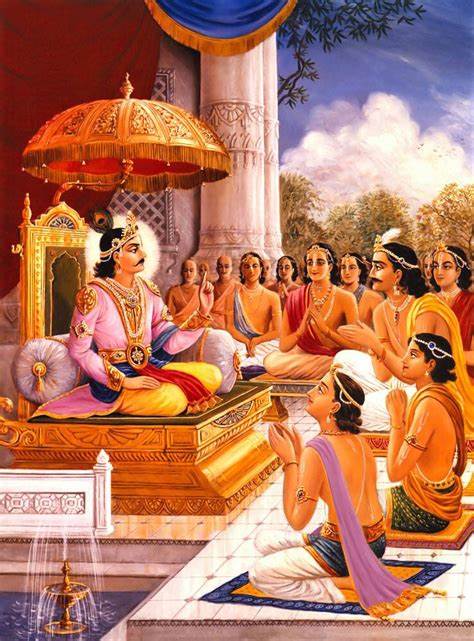

Next we have the example of the Pāṇḍavas. After the Kurukṣetra war, the Pāṇḍavas regained the throne of Hastināpura. But at the mature stage King Yudhiṣṭhira handed over the kingdom to his grandson Parīkṣit, quit household life “timely,” gave up all material attachments, and started “for the north”—that is, for the Himalayas and for going back to Godhead.3 The other Pāṇḍavas, as well as Draupadī and Subhadrā, followed the same path.

In the same dynasty, King Bharata, the son of Duṣmanta, had earlier handed over the throne and left family life. This king (for whom Arjuna is known as “descendant of Bharata”) had possessed immense opulence, and the Bhāgavatam says that his sons and family had seemed to him his entire life. “But finally he thought of all this as an impediment to spiritual advancement, and therefore he ceased from enjoying it.”4

Later, of course, Mahārāja Parīkṣit, when cursed by a brāhmaṇa boy, left everything and dedicated the last seven days of his life to hearing Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.5

Mahārāja Aṅga and Kardama Muni both renounced wife and home. Though perhaps the āśrama they adopted could better be called sannyāsa than vānaprastha, their behavior is instructive. Mahārāja Aṅga left home because his son, Vena, was a rogue,6 and Kardama Muni left home even though his son, Kapiladeva, was the Supreme Personality of Godhead.7

Dhruva, Prācīnabarhi, and Pṛthu

In the Fourth Canto, Dhruva Mahārāja at the end of his life leaves home and retires to Badarikāśrama and then goes back to Godhead.8 Similarly, King Prācīnabarhi, after hearing instructions from Nārada Muni, including the allegorical story of King Purañjana, leaves orders for his sons to protect the citizens and at once quits home for Kapilāśrama, where he attains perfection.9 As Śrīla Prabhupāda writes, “[W]hen Mahārāja Prācīnabarhi was convinced of the goal of life through the instructions of Nārada, he did not wait even a moment to see his sons return, but left immediately. There were many things to be done upon the return of his sons, but he simply left them a message. He knew what his prime duty was. He simply left instructions for his sons and went off for the purpose of spiritual advancement. This is the system of Vedic civilization.” The Fourth Canto also extensively describes the exemplary retirement of Mahārāja Pṛthu and his wife, Arci.10

Priyavrata, Nābhi, Ṛṣabadeva, and Bharata

In the Fifth Canto we find several examples of retirement. As the Fifth Canto begins, Parīkṣit Mahārāja asks how King Priyavrata, in spite of being attached to wife and family, attained perfection in Kṛṣṇa consciousness.11 Śukadeva Gosvāmī then describes how King Priyavrata entered householder life to honor the orders of his superiors and finally how he “reawakened to his senses,” divided his possessions among his sons, gave up family life, and attained perfection.12 Again we might say that the āśrama he accepted was not vānaprastha but sannyāsa, but again his history is relevant and instructive.

As the Fifth Canto continues, we hear that the Lord Himself, in the form of Ṛṣabhadeva, appeared as the son of King Priyavrata’s grandson King Nābhi.13 King Nābhi raised the son with great affection and with transcendental bliss, joy, and devotion and in due time installed Him on the throne. Then Nābhi and his wife retired to Badarikāśrama. There the King engaged in tapasya “with great jubilation” and absorbed himself in devotional service, and so he was elevated to Vaikuṇṭha.14

Just to set an example of how a father should instruct his sons before retiring from family life, Mahārāja Ṛṣabhadeva, after ruling the world, gave instructions to his one hundred sons. He then enthroned his eldest son, Bharata. Then Ṛṣabhadeva, though still at home, lived like an avadhūta, and finally he left home to travel the world.15 Ṛṣabhadeva’s son Mahārāja Bharata in turn handed over to his sons the kingdom he had inherited and retired from family life.16

Manu, other kings, Saubhari Muni, and the hunter

In the Eighth Canto (8.1.7) Svāyambhuva Manu gives up his kingdom for the forest with his wife, Śatarūpā.

In the Ninth Canto (9.1.42) we hear that King Sudyumna also handed over his kingdom to his son and entered the forest. So too did Mahārāja Ambarīṣa (9.5.26). We hear also that Saubhari Muni, despite having dedicated himself to the practice of yoga, fell into a life of material enjoyment but at the end he too became detached and became a vānaprastha, followed by his wives (9.6.52‒53). Similarly, King Yayāti, after a lifetime of excessive sense enjoyment, became “disgusted with sexual enjoyment and its bad effects” (9.19.1). He thus became renounced, and by his instructions, given through the story of a he-goat and she-goat, his wife Devayānī also “understood that the materialistic association of husband, friends and relatives is like the association in a hotel full of tourists.” Thus she too became detached and attained liberation (9.19.27‒28).

In the Eleventh Canto (chapter twenty-six) we hear of how Mahārāja Purūravā became detached from his desire to live with his wife Urvaśī.

Turning to Caitanya-caritāmṛta (Madhya 24.229‒282), we find the story of the hunter who, by the grace of Nārada, became a Vaiṣṇava and lived as an ideal vānaprastha, along with his wife.

The example of Śrīla Prabhupāda

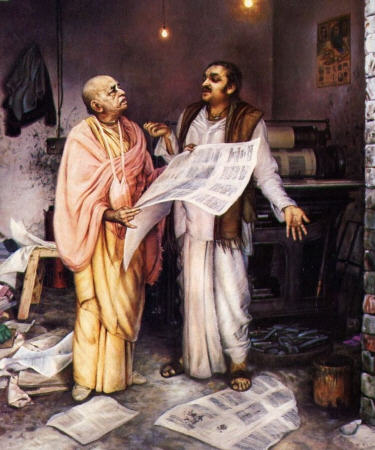

Finally we have the example of Śrīla Prabhupāda himself. As described in Śrīla–PrabhupādaLīlāmṛta, chapters 6 through 9, Śrīla Prabhupāda lived as a householder until 1950 and then retired from family life and lived as a vānaprastha until 1958, when he accepted sannyāsa.17

Śrīla Prabhupāda said that despite several indications given by his Guru Mahārāja he had been reluctant to give up family life. “I was thinking, ‘If I go away, then my family—my sons, my daughters—they will suffer.’” Nonetheless, he began vānaprastha life in 1950 and left home entirely in 1954. “But they are living; I am living. They are not dying in my absence, and I am not suffering without being in my family. On the other hand, by Kṛṣṇa’s grace, I have got better family members. I have got nice children in a foreign country. They are taking so much care of me, I could not expect such care from my own children. So this is God’s grace. We should depend on Kṛṣṇa. If Kṛṣṇa is kind, wherever we go, everyone will be pleased, everyone will be kind. And if Kṛṣṇa is unpleased, even in your family life you’ll not be comfortable. Therefore, according to the Vedic system, at a certain age, it is indicated that one should retire from family life.”18

Notes:

1 Bhāgavatam, First Canto, Chapter 13.

2 Bhāgavatam, Third Canto, Chapter 1.

3 Bhāgavatam, First Canto, Chapter 15.

4 Bhāgavatam 9.20.33. In the purport Śrīla Prabhupāda comments, “The Vedic civilization enjoins that after a certain age, following in the footsteps of Mahārāja Bharata, one should cease to enjoy material opulences and should take the order of vānaprastha.”

5 Bhāgavatam, First Canto, Chapter 19.

6 Bhāgavatam, Fourth Canto, Chapter 13.

7 Bhāgavatam, Third Canto, Chapter 24.

8 Bhāgavatam 4.12.16‒35.

9 Bhāgavatam 4.29.81‒82.

10 Bhāgavatam, Fourth Canto, Chapter 23.

11 Bhāgavatam, Fifth Canto, Chaper 1, texts 1‒4.

12 Bhāgavatam Fifth Canto, Chapter 1, texts 36‒38.

13 Bhāgavatam, Fifth Canto, Chapter 3.

14 Bhāgavatam 5.4.4‒5.

15 Bhāgavatam 5.5.28.

16 Bhāgavatam 5.7.8, 5.14.43‒44.

17 Śrīla Prabhupāda also mentions these dates in his Concluding Words to Śrī Caitanya-caritāmṛta. In a letter to Mahatma Dāsa (May 1, 1974) Śrīla Prabhupāda writes, “I was preaching and writing for eight or nine years as Vanaprastha and then in 1959 I took sannyasa.” The renunciation matters more than the date.

18 Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam lecture, September 12, 1969, Tittenhurst Park, UK.

This is part of a draft

This is an excerpt from a new book I have in the works—The Vānaprastha Adventure, a guide to retirement in spiritual life. While I’m working on it, I’ll be posting my draft here, in installments. I invite your comments, questions, and suggestions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.