What to Make of What You Find

Introduction

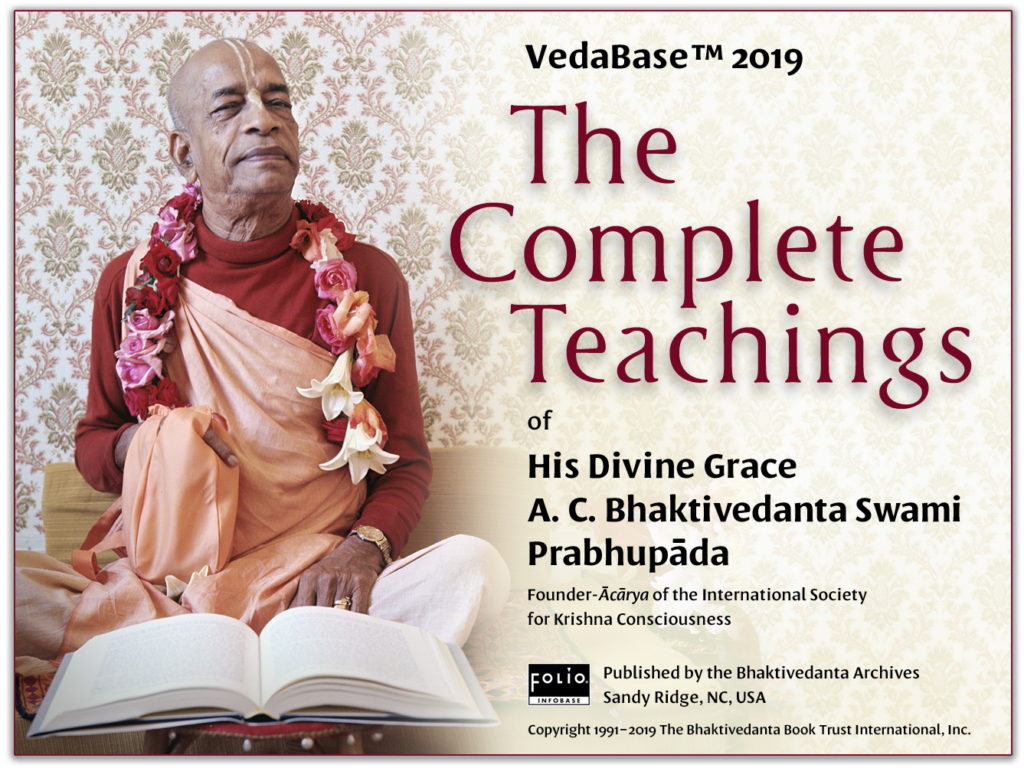

The Bhaktivedanta VedaBaseTM published by the Bhaktivedanta Archives is a powerful tool, and like all tools it may be used either well or badly. Used well, it can help us discover, gather, and bring to light many teachings the scriptures and Śrīla Prabhupāda give us. Used badly, it can help assemble false evidence, fallacious arguments, and wrong conclusions.

Here then is a brief guide to help you use the tool well. It’s not a guide to the software; that you’ll find elsewhere. Rather, it’s a guide to what to make of what the software gives you.

The followers of Śrīla Prabhupāda look to Śrīla Prabhupāda’s writings and spoken words as a source of knowledge and authority. As Śrīla Prabhupāda writes in Bhagavad-gītā As It Is, “The process of speaking in spiritual circles is to say something upheld by authority. One should at once quote from scriptural authority to back up what he is saying.” The scriptures have authority, and so too does the ācārya.

Therefore what we say gains strength when we can quote scripture or legitimately uphold our statements with the words “Prabhupāda said.”

But what Prabhupāda said sometimes differed. Sometimes he spoke for the benefit of an individual, sometimes for the world. Sometimes what he said was for the moment, sometimes forever. So as well as we can we need to recognize, in what Prabhupāda said, not only the content but the intent.

Śrīla Prabhupāda gave a cohesive and practical philosophy, the Vedic philosophy, clear and consistent in its conclusions. Merely searching through a database and collecting one’s “hits” cannot substitute for thoroughly and clearly understanding. Through service, inquiry, and a submissive attitude, one should try to understand the Vedic science under the guidance of the scriptures, saintly persons, and the bona fide spiritual master. This is the Vedic way to realize not only what the words of scripture and Śrīla Prabhupāda are but also what they mean.

Levels of Authority

To get the meaning right, it will be useful for us to look at the materials in this VedaBase as having different “levels of authority.” Here we are not making absolute divisions, but merely rules of thumb.

Books and formal documents

At the highest level of authority we can place Śrīla Prabhupāda’s books. These are the works in which Śrīla Prabhupāda formally presented for the world the message of the scriptures and the previous ācāryas. It is these books that form the very basis of the Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement.

There are other documents entitled to similar authority, in a different sort of way. These are legal documents in which Śrīla Prabhupāda gives explicit directions. Examples are trust deeds, incorporation papers, and his last will. Such documents were deliberate, purposeful, and clearly intended to be upheld by the full force of law.

Other documents, though not presented in the context of worldly law, are spiritual or managerial documents in which Śrīla Prabhupāda essentially “lays down the law.” An example would be the notice giving rules for initiated devotees that he put on paper on November 25, 1966, at 26 Second Avenue. These, clearly, are of a similar authority.

Lectures

At the next level, we can place Śrīla Prabhupāda’s lectures. These too, like his books, are formal public presentations.

Still, these speeches are extemporaneous. Śrīla Prabhupāda often speaks with no reference books before him, and with no chance to review or edit his words. So we may expect minor discrepancies—for example, a Sanskrit verse quoted imprecisely or a verse cited as being from one scripture when in fact it comes from another.

We may also need to take into account, here as in all of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s spoken words, that his first language is Bengali. In English, therefore, he sometimes uses one word when the meaning he intends is clearly that of another, or he uses the conventions of what students of language refer to as “Indian English.” Though this may take some getting used to, it should cause little confusion.

We may also take into account that each lecture has its own context. Each is spoken at a particular time and place and to a particular audience.

In fact, however, we see that wherever Śrīla Prabhupāda spoke, his conclusions were invariably the same; though the audience varied, his philosophy never did.

The question-and-answer portion of his lectures, however, deserves special attention. Here Śrīla Prabhupāda responds to the questions of specific individuals. Though again the philosophy is always the same, we cannot assume that how he speaks it to one person is how he would speak it to all. With one inquirer he might be stern, with another sympathetic, with one subtle, with another deliberately simple. We’d be rash to cite one instance as evidence of how he would respond in all instances.

Finally, we should note that in lectures, again as whenever Śrīla Prabhupāda speaks, there is the possibility of mistaken transcriptions. Though the lectures and conversations in this VedaBase have been carefully transcribed and reviewed, Śrīla Prabhupāda spoke with a strong Bengali accent, and minor errors in transcription are sure to have slipped through. This should be of little substantial consequence.

Letters

In the next category of authority, we come to Śrīla Prabhupāda’s letters. Here, more variables come into play. Śrīla Prabhupāda is again addressing a particular person, in a particular time and circumstance. And this time his words are sent in a sealed envelope, not spoken in a public assembly. His words, therefore, may be intended for many people or only for one. They may give instructions meant to apply always and to everyone or only to a special circumstance and one recipient.

Consider, for example, these various instructions:

“. . . this sankirtana or street chanting must go on, it is our . . . most important program.” (to Bali Mardana and Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa, September 18, 1972)

“Now the most important point is to recruit life members as many as possible.” (to Dayānanda, February 8, 1971)

“Now I very much appreciate your activities for conducting our school . . . and I consider your work the most important in the society.” (to Son and Daughters in Dallas, June 20, 1972)

“I consider this Mayapur Project to be our most important work. . . .” (to Tamāla Kṛṣṇa, June 28, 1972)

“The most important thing is that you must follow all of the rules and regulations very strictly.” (to Tapana Misra Dasa, May 26, 1975)

“There is no doubt about it, to distribute books is our most important activity.” (to Ramesvara, August 3, 1973)

Clearly, what Śrīla Prabhupāda chose to emphasize as “most important” differed according to the time, place, and person.

This is by no means to say that the instructions in his letters can simply be waved away as “relative.” But one must be careful to understand how, when, and to whom he intended them to apply.

A final concern about letters might be that some letters Śrīla Prabhupāda personally wrote or dictated, others he signed after a secretary composed them, and still others a secretary wrote and signed and Śrīla Prabhupāda countersigned as “approved.” Such a concern, however, should have little impact. All such letters have authority. Śrīla Prabhupāda’s signature shows his clear endorsement of whatever the letter might say.

Conversations

Now at last we come to Śrīla Prabhupāda’s conversations. Here, as in letters, again we have variables of time, place, and circumstance. In one sense, though, the conversations are more public, several devotees (often large groups) being in attendance.

But the full dynamics of a conversation are particularly hard to follow in print. Gone are the smiles, frowns, glances, and hand gestures that often tell more than the words. Gone the surroundings. Gone, most often, whatever was said before and after. What remains may be valuable—but it’s far from everything.

We should keep in mind, too, that in conversations with Śrīla Prabhupāda there may often be misunderstanding due to differences in language. Śrīla Prabhupāda may mishear what those he is speaking with have said, or they what he has said. The results are sometimes amusing, often confusing. We must take care, therefore, to make sure we have things right.

Levels of Authority, Summed Up

In summary, a quick chart of the levels of authority we might accord to the materials in this VedaBase, starting with the highest, could look something like this:

Books

Legal documents and similar papers

Lectures

Letters

Conversations

Again, this is merely a guideline, not a cast-iron standard. Letters and conversations may often give significant, even invaluable, knowledge and guidance not to be found anywhere else. And for the person to whom Śrīla Prabhupāda originally directed his words, they might be the most important words in the world.

What Makes Good Evidence

Now, we still need to use care, because good words can be used for bad arguments. So let’s set some ground rules, so that the good words will lead to good understanding.

Śrīla Prabhupāda’s words should not be unduly severed from their context

Śrīla Prabhupāda’s words have a context, and one should not wrench them out of context to make a point their context would belie.

For example, suppose you wanted to demonstrate that eating meat is acceptable, so long as one pays for it. You might quote this statement made by Śrīla Prabhupāda in a letter to Brahmānanda Dāsa (October 6, 1969):

As you will pay for the dinner, for the fooding, you can offer them to Krishna within your mind, then eat them as Krishna Prasadam. Any foodstuff when it is paid for, it becomes purified. There is a verse in Vedic literature, Drabyamulyena Suddhati. The source of receipt of the thing, may be not very good, but if one pays for it, it becomes purified.

There you have it: proof. But the next lines show the context, by which the supposed proof falls apart:

So, vegetable diet when it is paid for, you can offer it in your mind to Krishna and take it. But this Drabya means eatables, and eatables meaning vegetables, grains, milk, flowers, fruits; meat is not considered an eatable—it is considered untouchable. Just like if somebody purchases some stool, that does not mean it is now purified. So meat is like that. This Drabya means vegetables, etc.

It is pernicious to sliver sentences or carve into paragraphs to force them to say what you want. The words of an authority should be quoted faithfully to their context and to the meaning originally intended.

Words intended for a particular time, place, person, or circumstance must not be forced upon another

On October 7, 1970, Śrīla Prabhupāda wrote to Advaita Dāsa:

If there is any disagreement with your Godbrothers, you may live separately. That doesn’t matter.

“Just see,” one might say. “Living with one’s godbrothers is unimportant, and in the event of disagreement one is advised to live separately.” But then we have this letter, written to Ksirodakasayi dāsa on December 26, 1971:

I understand that you are not with the devotees. I do not know why you are living separately. In the Society there may be sometimes misunderstandings, but that does not mean you should live separately.

Thus to different devotees at different times and places, Śrīla Prabhupāda gave differing advice. The instructions given for one person at one time and place and in one set of circumstances may not be suitable for another. Or again they may.

So how well the instructions fit is a matter to be carefully discerned. Square pegs should not be pounded into round holes.

When quotations are cited as evidence, their meaning should be clear and unequivocal

When Śrīla Prabhupāda spoke or wrote, he was not, after all, intent on providing quotations for a database. So you may sometimes find a “hit” whose meaning is ambiguous or obscure. Under such circumstances, the honest thing to do is admit it. We should not try to bluff, presenting as definitive evidence a quotation whose meaning is fuzzy.

In order for a quotation to strongly support a point, the meaning of what we quote should be self-evident. If to get across what Śrīla Prabhupāda supposedly means we need profuse logical explanations, are we still arguing from authority, or from logic?

An argument from logic may sometimes be quite okay, but it should be seen for what it is: an argument from logic, or from logic and authority combined, not purely an argument from Vedic authority.

We should weigh a statement from Śrīla Prabhupāda carefully when we know he modifies or contradicts it elsewhere.

In The Nectar of Devotion Śrīla Prabhupāda writes:

One should begin the worship of the demigod Ganapati, who drives away all impediments in the execution of devotional service. In the Brahma-saṁhitā it is stated that Ganapati worships the lotus feet of Lord Nṛsiṁha-deva and in that way has become auspicious for the devotees in clearing out all impediments. Therefore, all devotees should worship Ganapati.

We can take this as clear and authoritative proof that Śrīla Prabhupāda wanted all the devotees in his society to worship Gaṇapati (Gaṇeśa).

But balance that passage against this letter to Śivānanda Dāsa (August 25, 1971):

So far worshiping Ganesa is concerned, that is not necessary. Not that it should be done on a regular basis. If you like you can pray to Ganapati for removing all impediments on the path of Krishna Consciousness. That you can do if you like.

And finally, consider this letter, sent to “My dear Sons” in Evanston, Illinois, on December 28, 1974. (Śrīla Prabhupāda sent nearly identical messages to several other devotees.)

I do not encourage you to worship this demigod, Ganesa. It is not required, it is not necessary. Simply worship Kṛṣṇa. Perform nice devotional service to Kṛṣṇa. Then your lives will certainly become perfect. Of course if one has got some sentiment for achieving the blessings of Ganesa for accumulating large sums of money to serve Kṛṣṇa, then he may perform this Ganesa worship, privately, not making a public show. But first of all he must give me $100,000 per month. Not a single farthing less. If he can supply this amount, $100,000 per month, then he will be allowed to do this Ganesa Puja. Otherwise he should not do it. It will not be good. That is my order.

Although the injunction to worship Ganesa is clear and comes from a book, in this case the evidence from the letters weighs in heavier.

Also worth taking into account here: All other things being equal (which they may not always be), a later instruction outweighs an earlier one.

Be careful when you count

One way to drive a point in is to make it again and again. So we pay special heed to statements made by Śrīla Prabhupāda or the scriptures repeatedly, many times over. For example: “You have to follow these regulative principles: no illicit sex life, no meat-eating, no intoxication, no gambling.” (lecture on Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, December 12, 1970) Śrīla Prabhupāda said this again and again, and clearly he meant it. When what you’re saying is backed up by such often-repeated instructions, you have a powerful case.

Note, however, that merely counting lots of “hits” doesn’t make your case strong. Your quotations should be true to their context, clear in meaning, free from contradiction elsewhere, and thoroughly relevant to the point you wish to make.

Evidence should be relevant

The quotations you offer must actually uphold what you’re trying to say. Otherwise, why are you quoting them? It’s not enough for a quotation merely to include the keyword you’ve searched for. That alone doesn’t make for relevance. The quotation should directly support your point.

Suppose, for example, you want to argue that in a society of devotees there ought to be no divorce. To support your case, you might quote as evidence this statement from Śrīla Prabhupāda’s purports to Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam (5.13.8):

In the Western countries, due to the dissatisfaction of the family members, there is actually no family life. There are many cases of divorce, and out of dissatisfaction the children leave the protection of their parents.

That’s a fine quotation. But it does virtually nothing to uphold the argument you wish to make. It says there are many cases of divorce, and many instances in which children leave their parents. But it says nothing to argue that there ought to be no divorce, and about divorce among devotees it is silent. So if you’re looking for evidence, this isn’t it.

You need quotations that go precisely to your point. Even though other quotations might be “hits,” they’re false hits—irrelevant—and you should put them aside.

Thoroughly understand Śrīla Prabhupāda’s teachings

Again, there is no substitute for thorough understanding. To use this powerful database most effectively, we should thoroughly understand Śrīla Prabhupāda’s message, the message of the Vedic conclusions. The way to understand that message best is not only to study it and cite it but to follow it.

Hare Kṛṣṇa.

You must be logged in to post a comment.