The Vānaprastha Adventure, Installment 8

One of my students asked me, “If vānaprastha life is meant to start sometime around the age of fifty, shouldn’t we be planning for it from the time we enter the gṛhastha āśrama in order to have an easier change?”

Actually the planning for the vānaprastha life should begin even earlier. For progress on the road of varṇāśrama, the first stage is brahmacārī life. A brahmacārī may stay brahmacārī or go directly to sannyāsa. But often the brahmacārī marries. And for married life, training as a brahmacārī provides the best foundation.1 Too often, though, we see that brahmacārī life is neglected or set aside as needless or impractical. Either as young men we skip it or as parents we drift over to a sort of child-rearing where we send our children to school (perhaps at best a “dharmic karmi” school), and then they get married, then have a career—and miss that initial training.

Brahmacārī guru-kule vasan dānto guror hitam:2 In brahmacārī life we learn how to control the senses, how to control the mind, how to become a person of character, how to live for the service of the spiritual master as a humble servant, and how to develop strong Kṛṣṇa consciousness.

With strong Kṛṣṇa consciousness, if I enter the gṛhastha life, then I have the substance with which to succeed in my householder duties. The husband is supposed to be the spiritual master of the wife, and when properly trained he has the spiritual assets with which to fulfill that role.3 And when the time comes to become a vānaprastha, the life of detachment will be something familiar for him to return to.

So brahmacārī life prepares one for gṛhastha life, and vānaprastha life, and the end of life. In the Bhagavad-gītā (8.5) Lord Kṛṣṇa says:

anta-kāle ca mām eva

smaran muktvā kalevaram

yaḥ prayāti sa mad-bhāvaṁ

yāti nāsty atra saṁśayaḥ

One who remembers Kṛṣṇa at the end of life goes back home, back to Godhead. That’s the goal of human life—ante nārāyaṇa smṛtiḥ: to remember Nārāyaṇa, Kṛṣṇa.4 That’s the goal we want to reach before the man blows his whistle and the game is over.

Preparing from childhood (and before)

In fact, preparing for this goal begins even before brahmacārī life. Shifting our view and speaking to parents: Preparing for a child’s life begins at the time of conception. In the Vedic culture the parents would perform the garbhādāna-saṁskāra—or for devotees in ISKCON Śrīla Prabhupāda instructed that prospective parents should chant fifty rounds of the mahā-mantra, to surcharge their minds with Kṛṣṇa consciousness with the intention of begetting a good Kṛṣṇa conscious child.5 During pregnancy the mother should especially hear transcendental sound. Śukadeva Gosvāmī and Prahlāda Mahārāja were hearing transcendental sound even from within the womb.

So in the Vedic culture, even before life begins one prepares the coming child for its full life. Then the child is born, and everything is done to try to surround the child with a Kṛṣṇa conscious atmosphere. Śrīla Prabhupāda, in his Dedication to the Krishna Book, wrote of his father, “He raised me as a Kṛṣṇa conscious child.”

A child, therefore, should be conceived and raised in Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Later, when children grow up, they may marry and enter the gṛhastha āśrama. And in the gṛhastha āśrama one should plan for what’s next. (If we’re young but we weren’t born and raised in a Kṛṣṇa conscious family, all right. Still we can join the brahmacārī āśrama and receive brahmacārī training, and then, if we marry, plan for what’s next.)

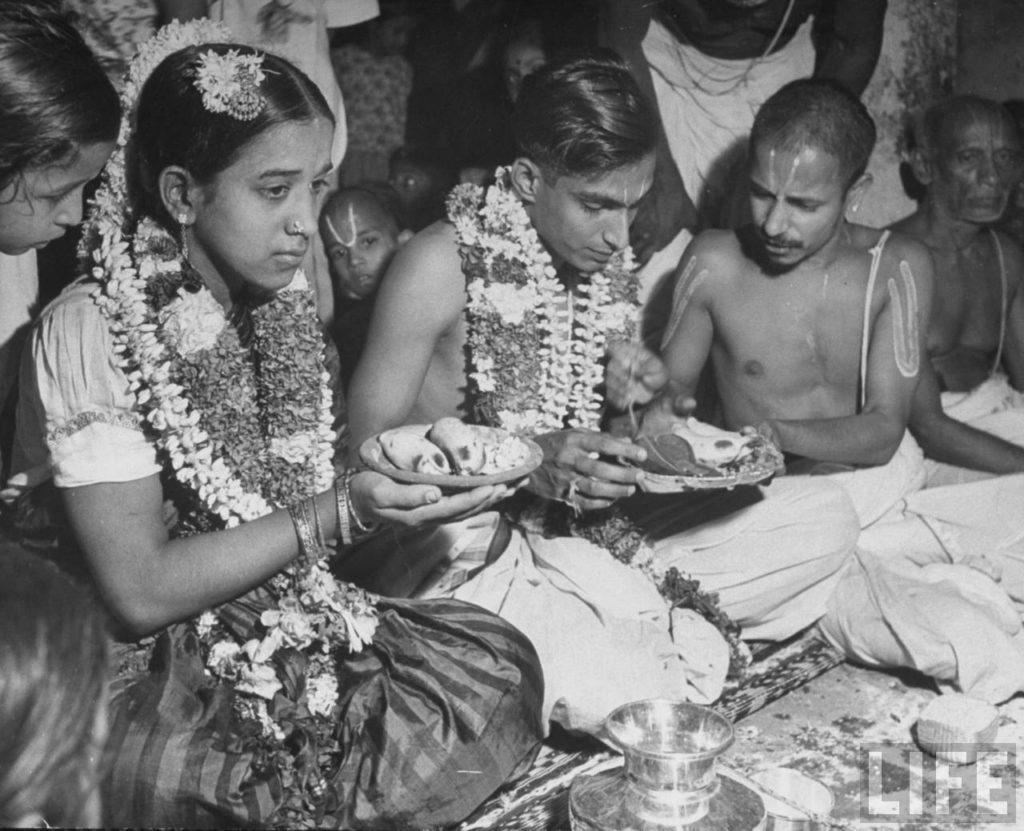

Marriage informed by the prospect of retirement

If we know that our life in the gṛhastha āśrama is at a certain point meant to end – if we know that one day we will leave it behind – we should make our plans for leaving. Of course, we don’t expect that on our wedding day our mind will be absorbed in plans for going to the forest. But leaving home should be part of our plan.6

Kardama Muni told Svāyambhuva Manu, “Yes, I’ll accept your daughter – until a son is born, and then the forest.” So the plan was in place from early on.7

Just as we know we’ll be young for a while and then sometime later be old, when we enter family life we should know, “We’ll live in married life for some years, and then we’ll be moving on to the next stage.” So this is something we should plan for.

In a business we make plans for succession. In our personal finances we save money for the future. So, in a similar way, during our family life we should plan how to graduate from the gṛhastha āśrama and move on to the āśrama that comes next. That will inform and benefit our gṛhastha life. With this in mind, we should make sure that our gṛhastha āśrama is genuinely an āśrama—that is, that it is centered around the holy name, the Bhāgavatam, and devotional service—so that our hearts become purified and when the time comes we’ll be ready to move on.

If my gṛhastha life is uninformed by the prospect of vānaprastha life, how can my gṛhastha life stay on course? When I don’t know where I’m going next, what I do now will be aimless. And if I think I’ll never go anywhere else but where I am, my life will be dead in the water. But if I know where I am and where I’m going, then I can plan. I can look and see, “How far along am I? And how do I make sure we’re moving toward our goal?”

Thinking ahead

As an example of thinking ahead, I can mention Vṛndāvana Candra Dāsa, a retired professor, an elderly Gujarati disciple of His Holiness Bhakti Chāru Swami living in New Jersey. In one of my vānaprastha seminars he told of how, as a gṛhastha, he had been thinking about one day moving into the temple after his sons were married and his job was over. Knowing that there would be austerities and difficulties but eager to serve, he was looking forward to being in the temple. And because he had a plan, the execution was relatively smooth. It was a natural transition.8

This sort of planning is both wise and essential. One should know, “I’m only going to be in householder life for a while. I’m only going to be in this world for a while. So I have to plan to make the project of my life a success.”

That will inform how we bring up our children also. If a son knows, “After some time I’ll be taking care of my mother,” that changes things for the child, does it not? As a young man he knows, “My parents have done whatever they could for me, and now I have my duties toward them.” This is the life of a responsible human being.

Gṛhastha life is a life of responsibility. The gṛhastha accepts the duties of gṛhastha life both for his own progress and to instruct his children, “Here are the duties we are all meant to take up.”

Knowing that after twenty-five years of family life I’ll have the duty to leave also tends to push family life into an earlier time frame. It argues against the modern norm of placing education and career first and then getting married at the age of thirty-something and having children when we’re thirty-five or forty. It argues back in the Vedic direction of girls getting married by sixteen or eighteen (or even earlier) and boys getting married in their early twenties.

Decision-making for brahmacārīs

Brahmacārīs living in an āśrama, of course, may also leave the āśrama and marry, and having this larger picture in mind can help inform their decisions as well. Happy brahmacārīs can stay brahmacārīs forever. But if a brahmacārī is inclined towards family life, best for him to take it up by twenty-five or so. Become a gṛhastha, have a family, and then at the right time move on. This is better than struggling on in brahmacārī life till thirty-something or later and then plunging into married life late in the game and still having a home with young children at the age when one ought to retire.

As for brahmacārīs who have already reached or passed thirty-something and who sometimes think of marriage, they may also benefit from remembering the larger picture. Such a brahmacārī might think, “Earlier, I might have gotten married. But if I marry now I’ll have to stay married into maybe my sixties or seventies. Since I’ve already stayed a brahmacārī this far, better to just stick with it.” Of course, each person’s life is different. But, again, this perspective can help inform one’s decisions. (It can also help inform those responsible for guiding brahmacārīs. We should think of their lives as a whole and not artificially try to keep every man a brahmacārī forever.)

It makes sense for gṛhasthas to have children early. Then when the time comes for the gṛhastha to become a vānaprastha, the children will already be adults. Having children when we’re in our forties or later, after many years of married life, doesn’t make a lot of sense. It’s like serving twenty years of a jail term and becoming eligible for parole and then punching the warden and getting stuck in jail for another twenty or twenty-five years.9

Get married, have your children, and then move on.

Notes:

1 As Śrīla Prabhupāda wrote, “Household life is for one who is attached, and the vānaprastha and sannyāsa orders of life are for those who are detached from material life. The brahmacārī-āśrama is especially meant for training both the attached and the detached.” Bhāgavatam 1.9.26, purport. Emphasis in original.

2 Bhāgavatam 7.12.1.

3 The wife is supposed to be an inspiration in Kṛṣṇa consciousness, and if she has been well trained at home she too becomes qualified for her role.

4 Bhāgavatam 2.1.6.

5 Letter to Śyāma Dāsī, January 18, 1969. Letter to Madhusūdana Dāsa from Tamal Krishna Goswami (as Śrīla Prabhupāda’s secretary), May 19, 1977.

6 “It is not that a gṛhastha should live at home until he dies.” Cc. Madhya 24.259, purport.

7 Bhāgavatam 3.22.19.

8 Interview with Vṛndāvana Candra Dāsa, vānaprastha seminar, September 3, 2020.

9 For family life as a prison, see Śrīla Prabhupāda’s translation of Bhāgavatam 5.18.10 and Prahlāda Mahārāja’s comparison of family life to a silkworm’s being imprisoned in a cocoon (Bhāgavatam 7.6.13). Of course, such comparisons are supposed to apply only until one becomes Lord Kṛṣṇa’s devotee (see Bhāgavatam 10.14.36). Nonetheless, for someone approaching retirement age but still inclined to sex life and begetting children such comparisons might stimulate helpful insights.

This is part of a draft

This is an excerpt from a new book I have in the works—The Vānaprastha Adventure, a guide to retirement in spiritual life. While I’m working on it, I’ll be posting my draft here, in installments. I invite your comments, questions, and suggestions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.